How DNA fingerprint left its mark on justice

Last week, he and his half-brother Leon Brown, who was serving a life sentence for the same crime, were released from a jail in North Carolina, after DNA from a cigarette butt at the scene was found to belong another man – Roscoe Artis. Artis lived a block away from the spot where the victim’s body was found and went on to rape and kill again.

McCollum and Brown – both of whom have learning difficulties – were 19 and 15 at the time of the killing. They were convicted on the basis of confessions which they later retracted. There was no physical or eye-witness evidence linking them to the scene and the men claimed they had made their statements under duress. The police did everything they could to ensure they stayed in jail; they suppressed exculpatory evidence and did not undertake any serious review of the case until the North Carolina Innocence Inquiry Commission got involved in 2010. If it hadn’t been for the cigarette butt, it is likely McCollum and Brown would have spent the rest of their days behind bars. Their release is being hailed as a dramatic example of DNA’s power to deliver justice, albeit 30 years late.

Strange symmetry

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

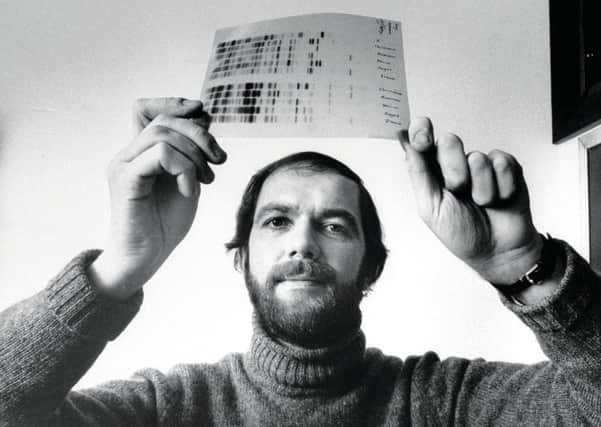

Thirty years. There is a strange symmetry in that figure. Because this Wednesday marks the 30th anniversary of the discovery of the genetic fingerprint. As the judge passed sentence on McCollum and Brown, in October 1984, thousands of miles away in a laboratory in Leicester, Professor Alec Jeffreys, was just beginning to develop the technology that would eventually free them.

Jeffreys’ eureka moment had come a few weeks earlier – at 9.05am on 10 September to be precise – as he looked at an X-ray he had made of genetic material from one of his technicians, Vicky Wilson.

He saw a fuzzy pattern and thought: “That’s a mess,” before realising this “mess” showed not only which parts of Wilson’s DNA came from her mother and which from her father, but also her unique genetic code. Jeffreys understood the implications of this discovery for criminal and other investigations. By the following week, he and his team were pricking their fingers and smearing blood on bits of paper to see if they could produce DNA fingerprints from this “evidence”. It quickly became clear they could.

Such was the demand for this new investigative tool that within a couple of years it was being used to solve crimes, aid immigration cases and establish the identity of skeletal remains. As the decades have passed, the technology has advanced; where once a substantial amount of bodily material (blood, semen, saliva, a strand of hair) was required, it is now possible to get results from microscopic amounts of DNA. It has turned crimefighting into a science.

Crucial role

DNA has played a crucial role in some of the highest profile cases of our time. Without genetic profiling, it is unlikely the killers of Rachel Nickell or Stephen Lawrence would ever have been brought to justice. It has also helped to exonerate the innocent, often – as with McCollum – retrospectively or even after death, but on occasion it has prevented charges being brought. Indeed, shortly after its discovery, it was used to establish Richard Buckland could not be the killer of two girls in the Leicestershire villages of Narborough and Enderby.

In Scotland too, DNA has often taken centre stage; it helped dismiss the theory that John McInnes, whose body was exhumed from Stonehouse Cemetery in Lanarkshire in 1996, was the notorious Glasgow serial killer nicknamed Bible John. And just last month, it helped convict former soldier John Docherty for the murder of Greenock teenager Elaine Doyle, 28 years ago.

DNA is now such a staple of crime novels and TV dramas like CSI, juries are often disappointed when the testimony brought before them is more prosaic: fingerprints, witness accounts or CCTV footage. But like all technology, DNA is a double-edged sword. Though its usefulness is not in contention, its collation and storage raises ethical dilemmas. For years, DNA samples were taken on arrest and stored in the National DNA Database regardless of whether or not the individual was later found guilty. Rulings from the European Court of Human Rights mean limits have now been imposed on the length of time samples from the unconvicted can be stored, but there are still more than 6 million profiles on the database in England and Wales (the rules in Scotland are much tougher). Jeffreys himself has warned authorities could use DNA to accumulate information on people’s racial origins, medical history and psychological profile.

Miscarriages of justice

On top of this, some fear the technology may be causing miscarriages of justice as well as preventing them. That’s certainly a concern for crime writer Val McDermid, who featured just such a scenario in her recent Tony Hill/Carol Jordan novel Cross And Burn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcDermid, a former crime reporter, has just finished writing Forensics: An Anatomy Of Crime – a non-fiction book which was commissioned by the Wellcome Trust to coincide with a forthcoming exhibition and will be published in October. “Because you can get results from such a small amount of DNA, it is perfectly feasible that there’s an entirely legitimate reason why a fragment of someone’s DNA should be on a piece of clothing or in a particular environment with no criminal implications whatsoever,” she says. “There are going to be situations where someone looks like a possible candidate for a crime and their DNA happens to be there for legitimate or accidental reasons and it will be very difficult for them to argue their way out of that.”

McDermid cites the Kafka-esque case of Adam Scott from Plymouth, who found himself remanded in custody in connection with a rape committed in a city he had never set foot. It transpired a plastic tray containing a sample of his saliva had been reused by a forensics team.

Human beings

“We mustn’t fall in love with the technology, we must always look at the technology in the context of the rest of the evidence and in the context of the human beings at the heart of it,” McDermid says.

Despite those reservations, it is difficult now to envisage the world without DNA testing. Almost from day one, it has been a key weapon in the investigator’s arsenal. Before his technology was used to solve the murders in Narborough and Enderby, Jeffreys found himself at the centre an immigration case involving a family from Ghana. He was asked to step in when the Home Office questioned the identity of a 13-year-old boy who had arrived in the UK to live with a woman he claimed was his mother. Though it was clear the pair were related, officials suspected he was really the woman’s nephew and threatened to deport him. With the father unavailable, establishing parentage was tricky. But Jeffreys found the boy’s DNA fingerprint contained 25 bands inherited from the woman, meaning there was only a one in 600,000 chance she wasn’t his mother. He then recreated the father’s DNA fingerprint by using strands in the couple’s three undisputed children and found half of the boy’s bands were a match. The Home Office accepted the boy’s identity and Jeffreys was tasked with telling his mother her son could stay.

Shortcomings

Successful though the immigration case was, it highlighted shortcomings in early genetic fingerprinting, so Jeffreys and his team refined the technology and came up with genetic profiling which made the DNA patterns easier to read and interpret.

Genetic profiling not only proved conclusively that Buckland was innocent of the Narborough/Enderby murders in 1983 and 1986 but that they were both committed by the same offender. So Leicestershire Police and the Forensic Science Service undertook an investigation in which 5,000 locals were asked to volunteer blood or saliva samples. The exercise took six months and no match was found. In August 1987, however, a man who worked in a bakery was overheard boasting that he had been paid £200 to give a sample while masquerading as his colleague Colin Pitchfork. The conversation was reported and Pitchfork was arrested. His DNA was found to match that of the killer and he was convicted of both murders in 1988.

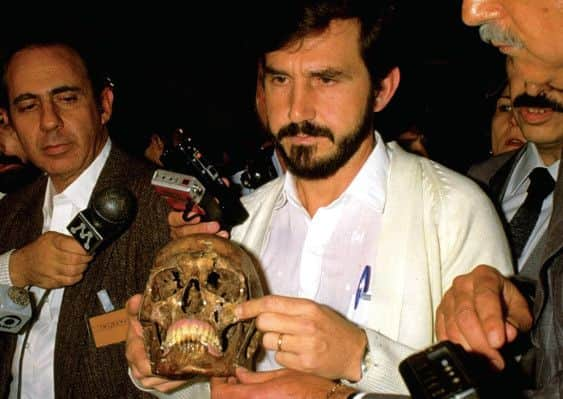

Jeffreys was also involved in a case which proved to be a precursor to the work identifying victims of mass war graves carried out by forensic anthropologist Sue Black and others. He was asked to establish whether bones uncovered in Brazil were indeed the remains of Auschwitz camp doctor Josef Mengele (they were).

Limited redress

With Rachel Nickell and Stephen Lawrence, DNA testing was able to provide a limited redress for appalling blunders in the initial inquiries. In the case of Nickell, who was murdered on Wimbledon Common in 1992, police had overlooked her real killer Robert Napper in favour of suspect Colin Stagg (who was later cleared). Napper was eventually convicted after small amounts of DNA found on Nickell were matched with his, but only after he had gone on to murder Samantha Bisset and her four-year-old daughter Jazmine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter a catalogue of police failures spanning 18 years, Gary Dobson and David Norris were finally convicted of the murder of Lawrence in 2012 on DNA evidence the defence said was “incapable of filling a teaspoon”.

McDermid says she doesn’t use a lot of science in her novels, but when she does she likes it to be authentic, often tapping Sue Black, who is a friend, for advice. “With my new book, The Skeleton Road, I knew I was going to be looking at the identification of skeletal remains. I rang Sue and found out it is now possible to tell [from analysing your bones] where your mother was living when she was pregnant with you. That information is in the book as part of the background, but it is also planted at the back of my head for a possible plot device for the future.”

DNA technology

DNA technology is advancing all the time. Earlier this year, the Home Office invested £431,000 in the development of Rapid DNA, a portable system which can be used at the scene of a crime and deliver results in a couple of hours as opposed to a couple of days.

But with advances come more ethical dilemmas. Take familial DNA testing, which started in the early 2000s. In 2006, police searching for a South Yorkshire sex offender dubbed the Dearne Valley Shoe rapist, because he always stole his victims’ stilettos, couldn’t find an exact match for his DNA so they started investigating 43 partial matches in the hopes they could track him down via a relative. On hearing they had knocked on his sister’s door, a man called James Lloyd told a relative he had committed a series of offences in his youth and attempted to kill himself. Police later found 100 pairs of stilettos under a trap door in his office. There are those, however, who see familial DNA testing as an infringement of privacy.

Innocent transference

Though the technology has uncovered many miscarriages of justice, there are also those who worry the general public places too much faith in its reliability. Recently Dr Michael Naughton, founder of the UK Innocence Project, warned of the risks of “innocent transference” which can happen if two people shake hands and so pick up traces of each other’s DNA. “I can then go into a pub that you’ve never been in or pick up a gun that you’ve never touched. I can shoot somebody with that gun and your DNA will be on that gun because I’ve transferred it. The public doesn’t know these things,” he said.

Yet for the likes of McCollum and Brown, DNA testing has offered the only hope of liberty. “I knew I was going to be blessed to get out of prison some time,” McCollum said last week. “I just didn’t know when that time would be.” «

• Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1